Kejawen (literally: ‘Javanism’, or Agama Jawa) is the original Javanese religion, which has been practiced since immemorial times in Java and today is a syncretic faith that mixes elements of Hinduism and Islam together with the ancient Javanese beliefs.

Kejawen is a metaphysical search for harmony within one’s inner self, a connection with the Universe, and ultimately with God.

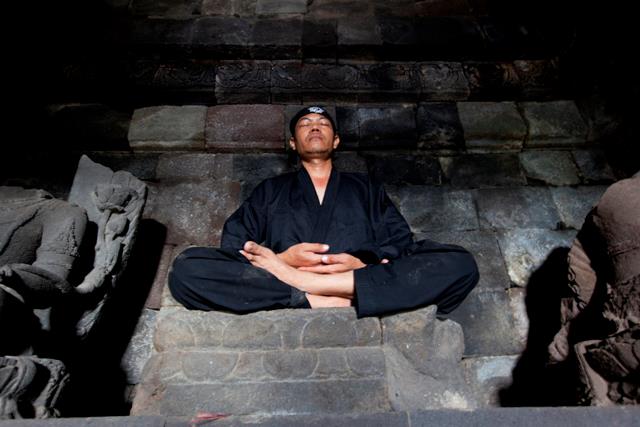

Kejawen practitioners believe in a “super-consciousness” which can be contacted through meditation.

The aim of the Javanese mystical tradition is that of experiencing unity with God, just like in Shaivism, Taoism and other Asian religions.

The Javanese mystical tradition is known for its syncretism, flexibility and pragmatism.

In the course of its history it absorbed all the religious traditions that reached Java and gave them it its own interpretation.

While Kejawen is distinct from the later Javanese Hinduism, it presents so many similarities in its worldview and concepts that the two merged harmoniously and seamlessly in Java for 2,000 years, due to a similar spiritual background.

Central and East Java are the strongholds of the Javanese religion today.

Core beliefs of the Javanese religion

Kejawen is a metaphysical search for harmony within one’s inner self, connection with the Universe, and with God Almighty that is to be contacted via meditation.

Javanese beliefs embody a “search for inner self” and “peace of mind”.

Javanism is in search of the most correct way of life, to find the spiritual way to true life (urip sejati) achieving the harmonious relation between servant and God.

Hence the saying, Jumbuhing Kawulo Gusti (jumbuh = a good, harmonious relation, kawulo = servant, gusti = Lord, God).

Kejawen emphasizes upon acting right, not because of the fear and intimidation of “sin” or “hell”, but because of a cosmic awareness that every good deed done to others is actually done towards oneself.

Kejawen teachings encourage one to never calculate the reward in every action. Good deeds should be done for their own sake, not because of seeking the rewards of heaven.

In Kejawen, kindness to others is seen as a need. Goodness will bear goodness and every good we do for others will return to ourselves.

Likewise, every evil action will bear evil too. If we complicate others’ lives, then in our affairs we will often find difficulties as well. If we love to help others, then our lives will tend to get easier.

Image source: Javanese Wisdom & Healing

Ensuring the harmony of microcosm and Macrocosm

In Kejawen, worship is a way of expressing gratitude to God, not a way to obtain something for oneself.

Kejawen teachings consider that gratitude to God through prayer is not enough – it must be implemented under the form of good actions for others.

If God gives health to someone, then as a form of gratitude the person must help others who are sick or suffering.

Kejawen teachings emphasize the relationship of microcosm and Macrocosm.

Man is part of the Cosmic whole. In true Javanese culture, spirituality is seen as the priority of an entire culture, pervading every aspect of life.

Yet in the last decades, many things have changed and society is rapidly moving toward base materialism and islamism.

In many villages, however, the traditional knowledge is still preserved.

Mamayu Hayuning Bawono

One of the most fundamental Javanese values is Mamayu Hayuning Bawono – a triple principle of harmony:

- the harmonious relation between human beings and Nature

- the harmonious relation among people in the society

- the harmonious relation between man and God

To preserve the beauty and harmony of the world is an imperative. By nature, a Javanese is a preserver of nature, an environmentalist.

The basic lesson of Kejawen is totally surrender to God as the source of everything (Sangkan paraning dumadi) and living harmoniously with all living and non living things of this Universe.

As you may have noticed, Memayu hayuning bawono is the exact equivalent of the Balinese philosophy of Tri Hita Karana, since both come from the same ancient Javanese source.

“To Javanese mystics life on earth is part of this all-pervading unity of existence. In this unity, all phenomena have their place and stand in complementary relationships to each other, they are part of one great design”. – Niels Mulder, Mysticism in Java

The keris is a central element of Javanese culture and Kejawen ritual practices

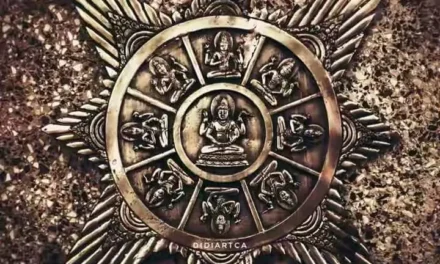

Javanese spirits and deities

The deities (dewata) of Kejawen are very similar to the Hindu-Buddhist deities known all over South and East Asia, and are sometimes known under their ancient Javanese names and sometimes under their ‘official’ Sanskrit names.

For example, Dewi Sri comes from Sri Devi, the consort of Vishnu, the Mother Goddess – often wrongly though of as merely “the goddess of fertility and rice”.

Only one character in Kejawen cosmology does not seem to have a clear Hindu equivalent.

Semar is the Divine Trickster acting as an intermediary between the gods and man, and in the wayang, he is a clown who is servant and guardian to the heroes of the Baratayuddha (the Javanese version of the Mahabharata).

Spirits are central to the Javanese religion, as they are all over Southeast Asia. They include ancestral spirits, guardian spirits of holy places such as old wells, old banyan trees, and caves. There are also ghosts, spooks, giants, fairies, and dwarfs.

The knowledge of the world of spirits in Java is unsurprisingly similar to that of the Philippines and of Thailand.

Semar, the guardian spirit of Java, in front of a Shiva statue in a Hindu-Kejawen shrine

Javanese meditation and spiritual practices

In Kejawen, human beings are understood as having an unconscious intelligence which surpasses their faculty of reason, and can deal with complexity more effectively.

From a Kejawen perspective, a person who is able to get deeply into the realm of spirit (alam gaib) is believed to have access to a higher form of intelligence that may seem supernatural to others.

The advanced Kejawen practitioner knows the world because he becomes the world, he then knows it from the position of an immanent subject whose spirit is in communion with, or identical with, the spirit of the Universe.

Kejawen spiritual practices include tiraka and tapa or tapabrata.

These practices are performed at home, in secluded caves or on mountain perches. Meditation is highly practiced in Javanese culture as a search for inner self wisdom and to develop personal strength.

Apart from traditional meditation, special practices include:

- Tapa Ngalong (meditation by hanging from a tree)

- Tapa Kungkum (meditation under a small waterfall or at the meeting point of 2-3 rivers.

Fasting is practiced by Javanese spiritualists in order to attain discipline of mind and body to get rid of material and emotional desires:

- Pasa Mutih (abstention from eating anything that is salted and sweetened, only eat/drink pure water & rice),

- Pasa Senen-Kemis (fasting on Monday-Thursday)

- Pasa Ngebleng (fasting for a longer period, usually 3-5-7 days)

The Javanese fasting is a movement to sense the ascetic (Laku pasa) and solitary meditative act to sense the personal space with self (Laku tapa).

Other ascetic practices include:

- Tapa Pati-Geni (avoiding fire or light for a day or days and isolating oneself in dark rooms),

- Tapa Ngadam (stand/walk on foot from sunset till sunset, 24 hours in Silence)

The techniques used are diverse: some groups meditate through use of mantra, others by concentration on a particular chakra, or do Tirta Yoga (immersion in holy waters).

Kanuragan is a secret ritual initiation tied to local cosmological practices and cults used by the Javanese as a source of self-help on issues related to health, welfare, and protection.

At basic levels, the practitioners of kanuragan use special entities called aji to gain strength and invulnerability.

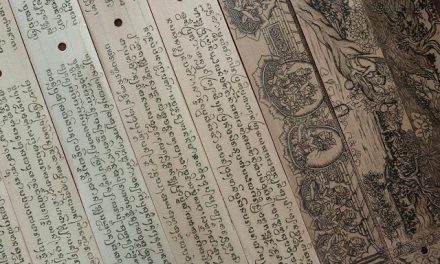

The sacred Kawi language

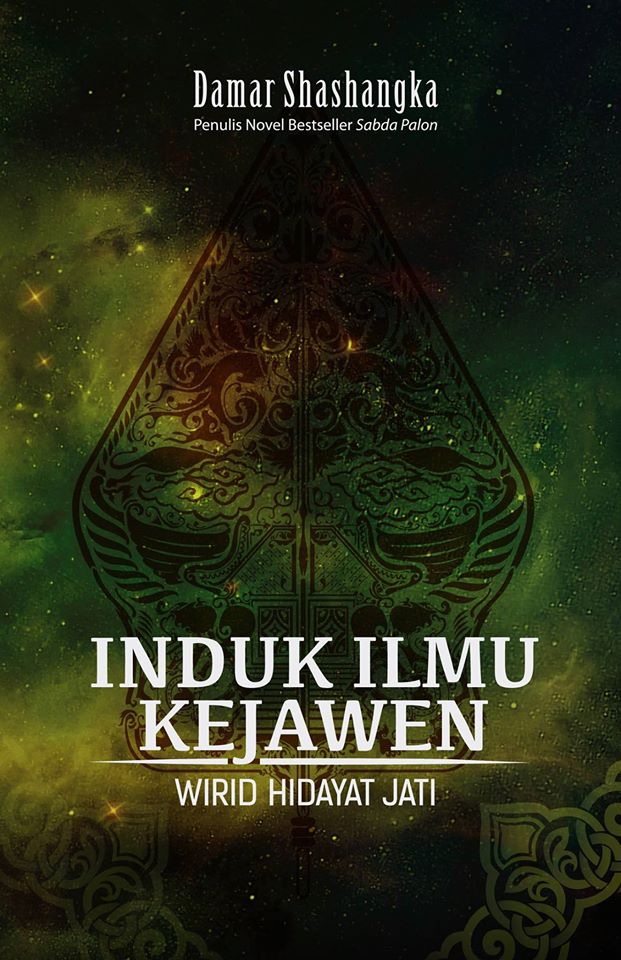

The most important Kejawen work is the 17th century Dewaruci, which expounds a mystical pantheistic view.

This view later became colored with Islamic concepts by those who wrote the Serat centhini and the magico-mystical Suluk books.

Kejawen practices are described in texts kept in the Sonobudoyo library in Yogyakarta, and the Kraton Libraries of Surakarta and Yogyakarta.

The Kejawen scriptures are deliberately obscure so that those who do not practice under the guidance of a teacher are unable to understand the esoteric doctrines.

True Kejawen practitioners use the sacred Kawi (Old Javanese) language as a medium for oral spiritual transmission.

Kawi is very close to Sanskrit and share many of the same words, such as:

- Susila = chaste, ethical

- Budhi = intelligence

- Dharma = divine law, customary observance.

- To live according to one’s dharma is to fulfill “the will of God” (kodrat).

- Wisdom (wicaksana), psyche (waskita) and perfection (sempurna).

The Gunungan is one perhaps the main symbol of Javanese culture and religion

External Kejawen rituals and ceremonies

Kejawen, just like Hinduism and Buddhism and all Asian religions in general, integrates sacrifices and offerings made to spirits of the land and ancestral spirits.

- Kemenyan is the offering of incense and flowers to communicate with spirits of the dead to gain peace of mind, solve problems in life or cure diseases. Offerings are made every kliwon, or once every Javanese five-day week.

- The Selametan ritual, a communal feast which symbolizes the mystic and social unity of all those taking part, which includes spirits, ancestors and gods.

- Bersih désa (“cleansing of the village”) ritual

- Sacred ritual dances such as the Bedaya Ketawang

- Collective offerings of large-scale mounds of fruits and vegetables, and animal sacrifices.

But beyond all that is the heart of the Javanese philosophy aimed at achieving harmony and balance in all things.

Conical offerings in the shape of Mount Meru

The Selamatan and the Cosmic Mountain (Gunungan)

The selamatan is the communal feast from Java, symbolizing the social unity of those participating in it. It the core ritual in Javanese culture.

The feast is also common among the closely related Sundanese and Madurese people.

A selametan can be given to celebrate almost any occurrence, including birth, marriage, death, moving to a new house, etc.

The selamatan is also held at specific dates such as the third, seventh, fortieth, hundredth, and thousandth anniversary of the decease of a relative.

The food eaten is meant to be a sacrifice for the soul of the dead person. After a thousand days the soul is supposed to have disintegrated or reincarnated.

The central element is the tumpeng – a rice cone cooked in turmeric – which refers to the ancient Indonesian tradition of revering mountains as the abode of hyangs, the gods and spirits of the land.

More importantly, the cone-shaped rice mimics the Cosmic Mountain.

In Java and Bali, the cone-shaped tumpeng symbolizes the glory of God as the Creator of nature, and the side dishes and vegetables represent the life and harmony of nature.

After the people pray, the top of the tumpeng is cut and given to the most important person in the assembly, or the one that is honored that day.

”The selamatan is a harmonizing ritual which is part of Javanese cosmology, where “man is surrounded by spirits and deities, apparitions and mysterious supernatural forces, which, unless he takes the proper precautions, may disturb him or even plunge him into disaster.” (J. M. van der Kroef)

Nasi Tumpeng, the famous conical dish of rice with turmeric in the shape of Mount Meru, placed in a lotus made of banana leaves

Javanese cultural practices

Javanese mysticism also reveals itself in daily activities. It is all about life in the world and human relation with himself, others, and the universe.

Before the development of formalized Hinduism, the Javanese had already a culture and belief(s) of their own.

Even during the 15 centuries of Hindu-Buddhist civilization, most Javanese were Kejawen practitioners rather than purely Hindu.

• The puppet figures in Wayang are based on the Javanese Mahabharata, although the figure of Semar in Wayang predates Javanese Hinduism.

The original Wayang was much more beautiful, but Islam banned the human form, causing the puppets to become ugly and grotesque, unlike humans.

They became so stylized that they are symbols rather than actual human figures.

• Batik came from Orissa in the 12th century. For seven centuries it was the preserve of women in royal families, who regarded it as a spiritual discipline and form of meditation.

The symbols used in batik designs are endless and include ancient stylised symbols as well as traditional, Indian, Chinese, and European motifs, which vary from region to region.

For example, the people of Java knew the wet-rice cultivation since 3000 years BC. This system of agriculture requires a smooth cooperation between villagers, to organize such a complicated arrangement and to benefit all parties involved.

Among other Javanese cultural practices are also the mystical gamelan music and the science of astronomy.

Kejawen organizations

Umbrella organisations representing Kejawen practitioners are registered at the HKP (Himpunan Penghayat Kepercayaan).

Among the most important Kejawen organizations are Sumarah, Sapta Dharma and Majapahit Pancasila.

- Sumarah theology maintains that humankind’s soul is like the holy spirit, a spark from the Divine Essence, which means that we are in essence similar to God. In other words, “One can find God within oneself,” a belief similar to the “I=God” theory of Hindu-Javanese philosophy. Sumarah is a philosophy of life and a form of meditation based on developing sensitivity and acceptance through deep relaxation of body, feelings and mind. Its aim is to create inside our self the inner space and the silence necessary for the true self to manifest and to speak to us. Sumarah means “total surrender”, a confident and conscious surrender of the partial ego to the Universal Self.

- Sapta Dharma – In Sapta Dharma teachings, suji (meditation) is necessary to pierce through different layers of obstacles to reach Semar, the guardian spirit of Java. Theory and practice resemble Hindu Kundalini Yoga, aiming at awakening the Kundalini energy and guiding it through the chakras.

- Majapahit Pancasila – Based in Hindu-Javanese yogic practices such as Kundalini yoga.

- Other groups exist that practice the powerful Hindu Kejawen.

- In Singapore, Kejawen is widespread among the Javanese Silat and Kuda Kepang groups, and traditional shamans.

There are hundreds of streams of Kejawen in which the emphasis in the teachings is different. Some are clearly syncretic, while others try to conform to a particular religion’s teachings. Some of the Kejawen spiritual movements lean more towards Arab Islam and have tense relations with the true Javanese schools, who jealously guard the secrets of Javanese magical practices such as kanoman (occult practices that give invulnerability to knives and guns).

Struggle for recognition

Kejawen is thousands of years old and is quintessential to Javanese culture. But that doesn’t necessary mean it’s accepted.

Social pressure in an islamized Java means that the practitioners are often told to convert to “the right path”, meaning the imported religions.

Kejawen is a flexible, open-minded and highly adaptable religion. There are no mandatory scriptures nor prophets.

It thus differs from the rigid, dogmatic attitudes of the Abrahamic religions.

Kejawen teachings are not glued to strict rules, and emphasizes the concept of balance. They are based on real experience, not rigid dogma written in books.

Thus, Kejawen teachings have always adapted to the perspective of the imported religions. Today, Kejawen practitioners can be Moslems, Hindus, Buddhists or Christians.

However, after the 1960s, under government pressure, many Javanese were forced out of their ancestral religion and other authentic Indonesian religions, and forced into the imported Abrahamic religions like Islam, Catholicism or Protestantism.

A significant minority then chose to revert to Javanese Hinduism instead.

The total number of Kejawen followers is therefore difficult to estimate, as their adherents have to identify themselves by law with one of the six ”official religions”.

For decades, members of the native Indonesian religions struggled to receive even basic government documents like marriage and birth certificates, and even passports, because the state wouldn’t recognize their religion.

This makes it difficult for them to access healthcare, education, and other social services to this day.

Some official Kejawen groups such as Sumarah do exist, although they failed to attain official recognition as a religion.

In 2017 Kejawen was finally indirectly recognized as being part of the Kepercayaan, a category which includes all the native religions of Indonesia.

Creeping islamization and discrimination in modern Java

Java is officially 90% Moslem, although only 20% follow Arab Islam, 40% follow Islam Nusantara, 30% follow a more or less islamized version of the Agama Jawa, while tens of millions are only nominal Moslems for legal reasons and social pressure.

But since the fall of Suharto – a secular dictator that kept political islam under his boot – and under the pressure of Middle Eastern propaganda, the trend is towards islamization.

The radical Moslems reject the ancient Asian beliefs in the unity of man and God and condemn Javanese rituals such as Wayang performances, keris rituals and selamatans.

As a result, the followers of the original faith are wrongly seen by the modern Indonesian mainstream as ‘backwards’.

By sticking to their spiritual tradition, Kejawen practitioners can suffer a lifetime of discrimination for following their own ancestral faith in their own land.

This pressure to rid Indonesian Islam of Hindu-Javanese elements had started at the end of the 19th century, with the more frequents travels of prozelityzers to and from the Middle East.

Arab Islam is popular today among the rootless city dwellers and the Javanese migrants to other provinces (from the transmigration program) who are disconnected from their Javanese roots, and among the uneducated masses that have the most children, which puts an increasing pressure upon true Javanese culture.